week2 How the platform constructs and holds power

Content Review

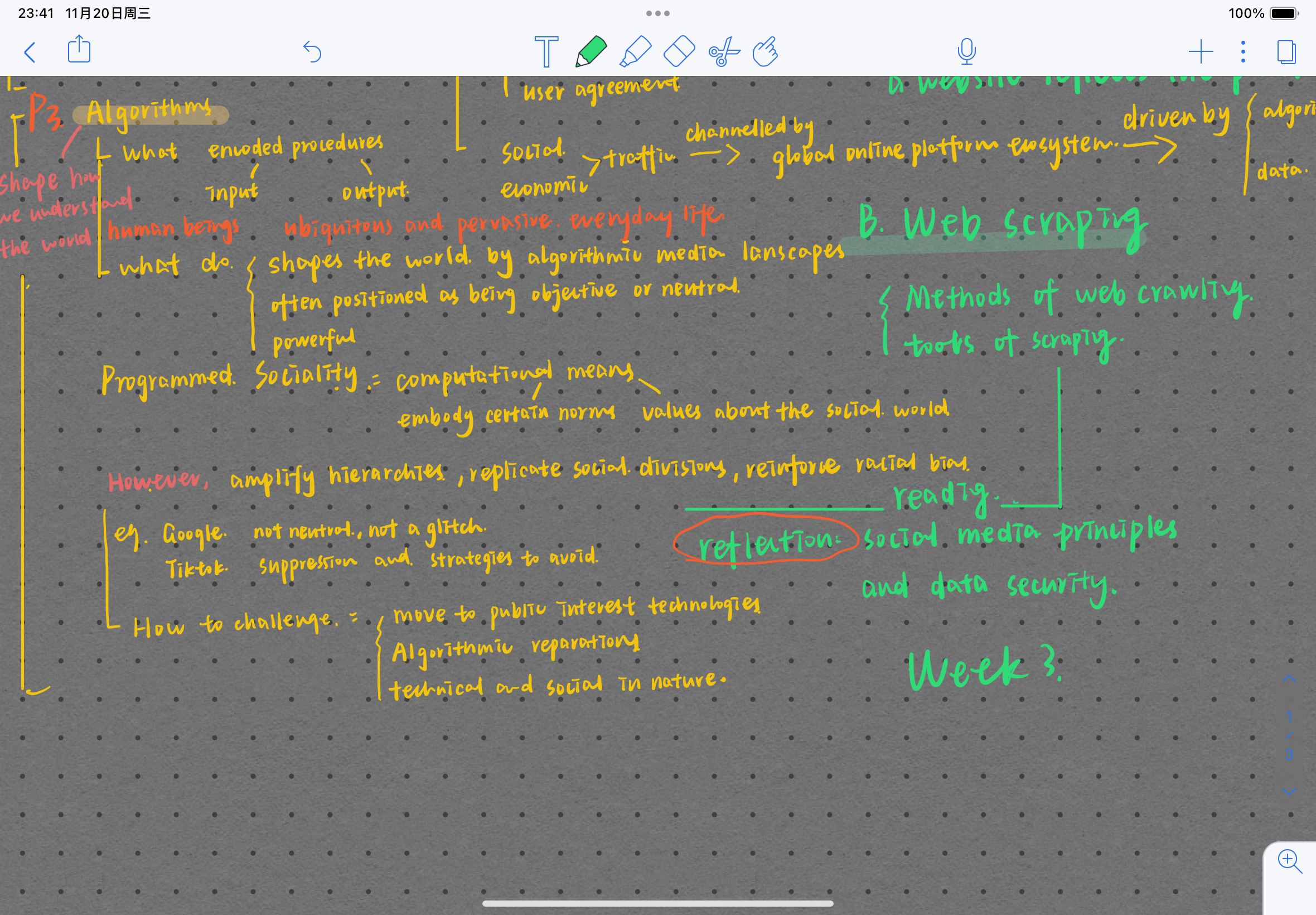

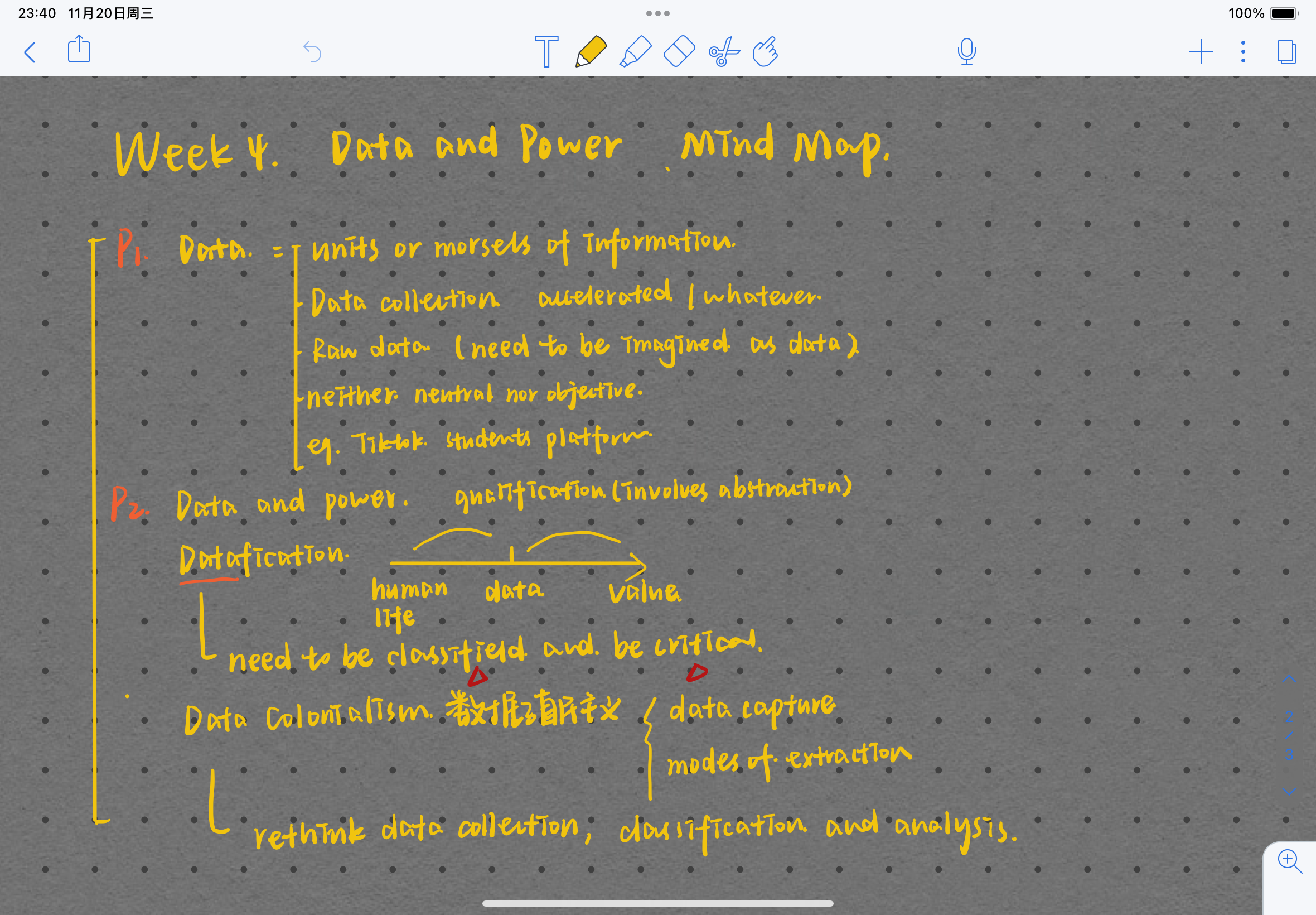

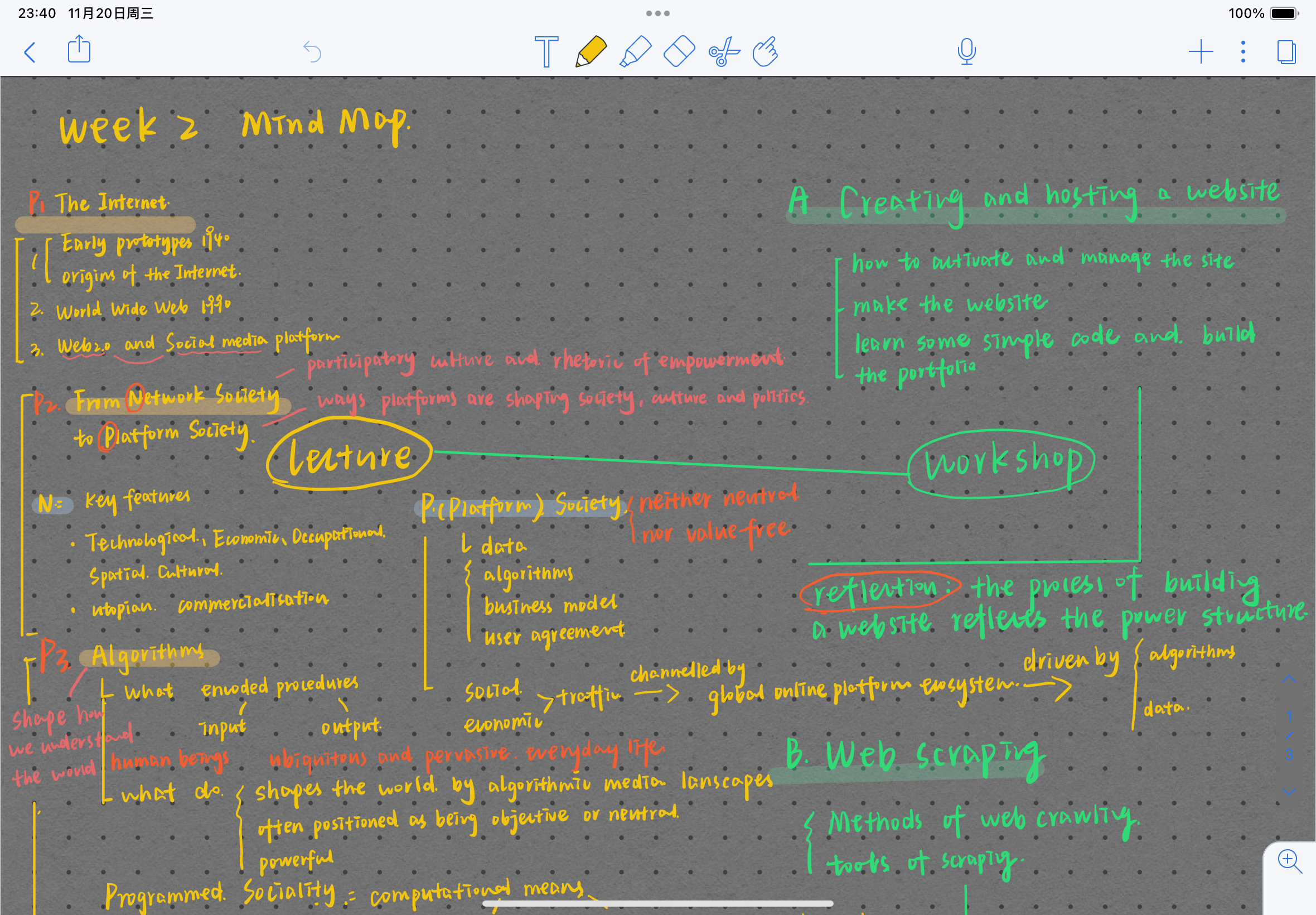

Thelecture of the second class contains three parts: the development of the Internet, from network society to platform society, Algorithms.In the workshop of the second week we learnt how to build a web page, in this class the teacher introduced us to HTML and CSS, and how to upload In this lesson, the teacher introduced us to HTML and CSS, and how to upload a web page to the server. In this lesson, I tried out some basic code and understood the basic process of building a website.

My Reflections

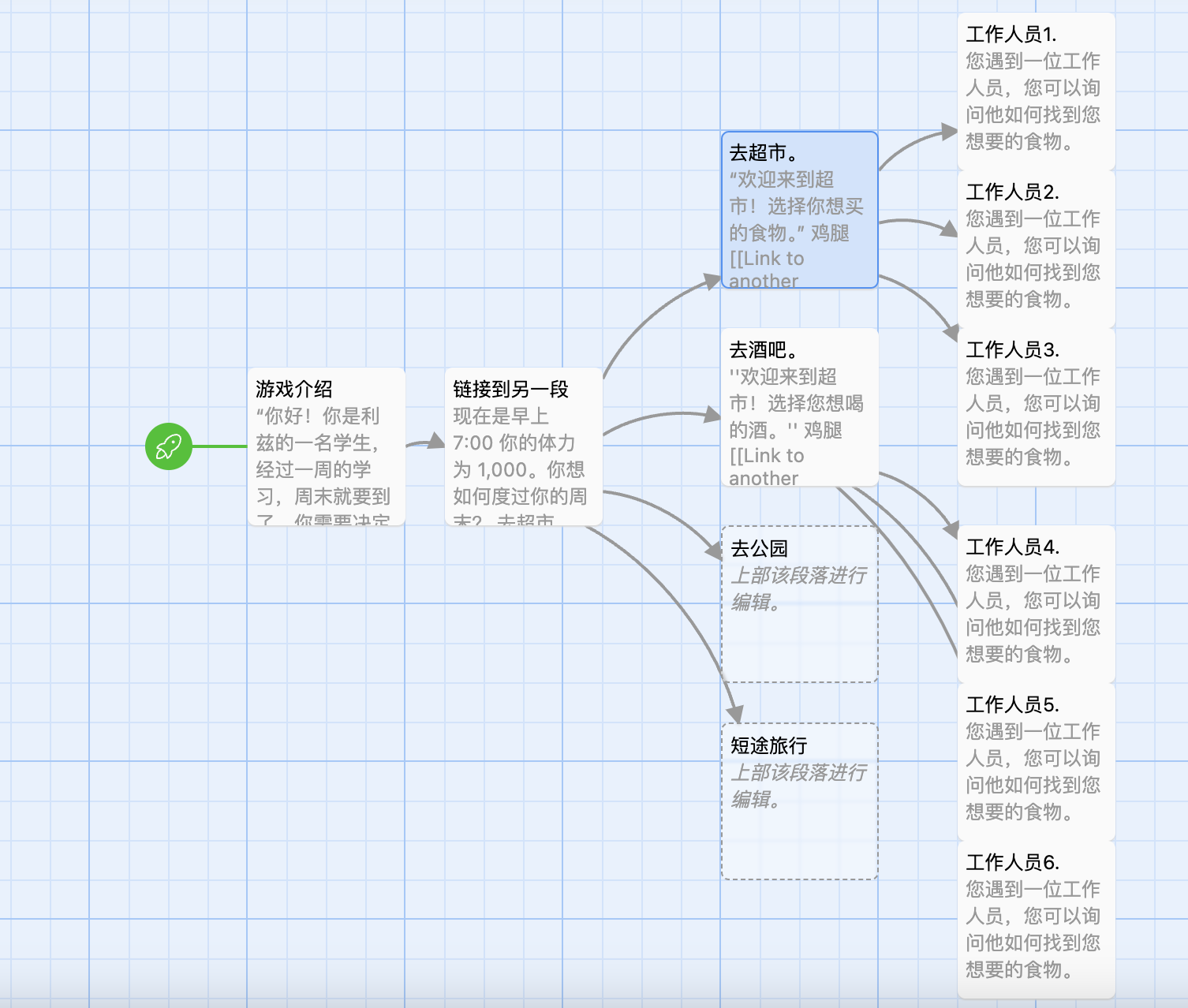

One of the things that gave me more food for thought was the understanding of platforms. When I tried to build my own website in workshop, I noticed that it was a 0 to 1 process, which means that excluding the content of the website itself, the structure of the website, the colours, the way it interacts and the way the modules are arranged are all determined by the builder of the webpage. For example, when I decide to place the profile more prominently, it directs the viewer's attention to this section first, while other sections may be ignored, so I essentially have control over the user's attention and behaviour.

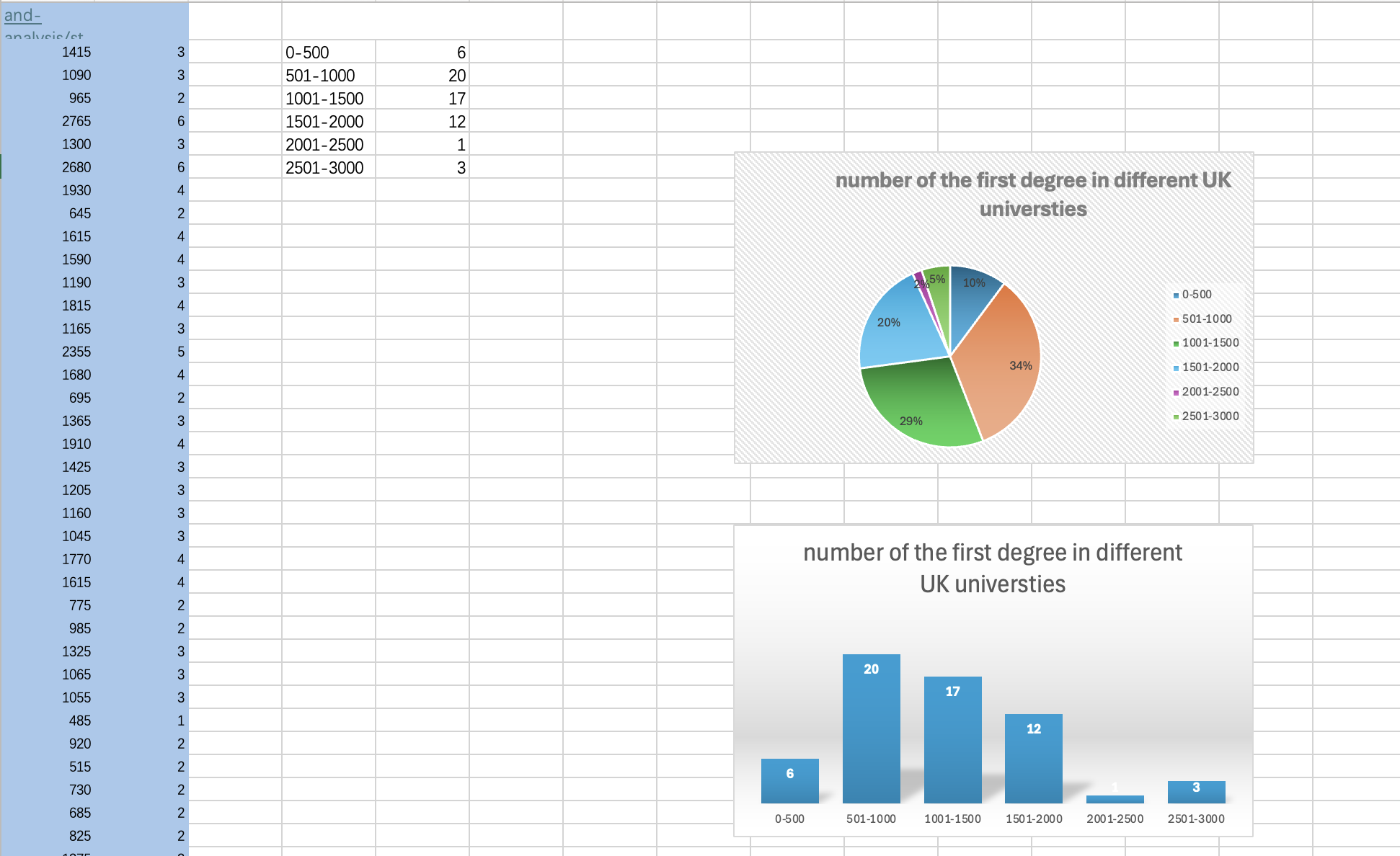

More notably, when I myself use social media or other online platforms in my daily life, I only focus on the content and the interaction with others, and rarely notice the power that the platforms have. This power structure manifests itself in many ways: the information architecture of the page, the visuals, the control of the algorithms, the collection of user data, and the guidance of emotions and behaviours. For example, when we open tiktok, the smooth video content instantly captures our attention, and when we comment, like and retweet, our clicks become data that the platform can access and analyse, and the platform readjusts its algorithms based on the analysis of the big data in order to further increase user interest and improve user stickiness.

Connecting with READING and exploring further

As (Hoffmann, 2018) argues, the explosive growth of expressive platforms requires us to rethink what a platform is and to think more about the power of platforms in society. When we talk about the platform society, we realise the inextricable relationship between online platforms and social structures (Dijck et al., 2018).

By reading Dijck et al.'s ’The platform society : public values in a connective world

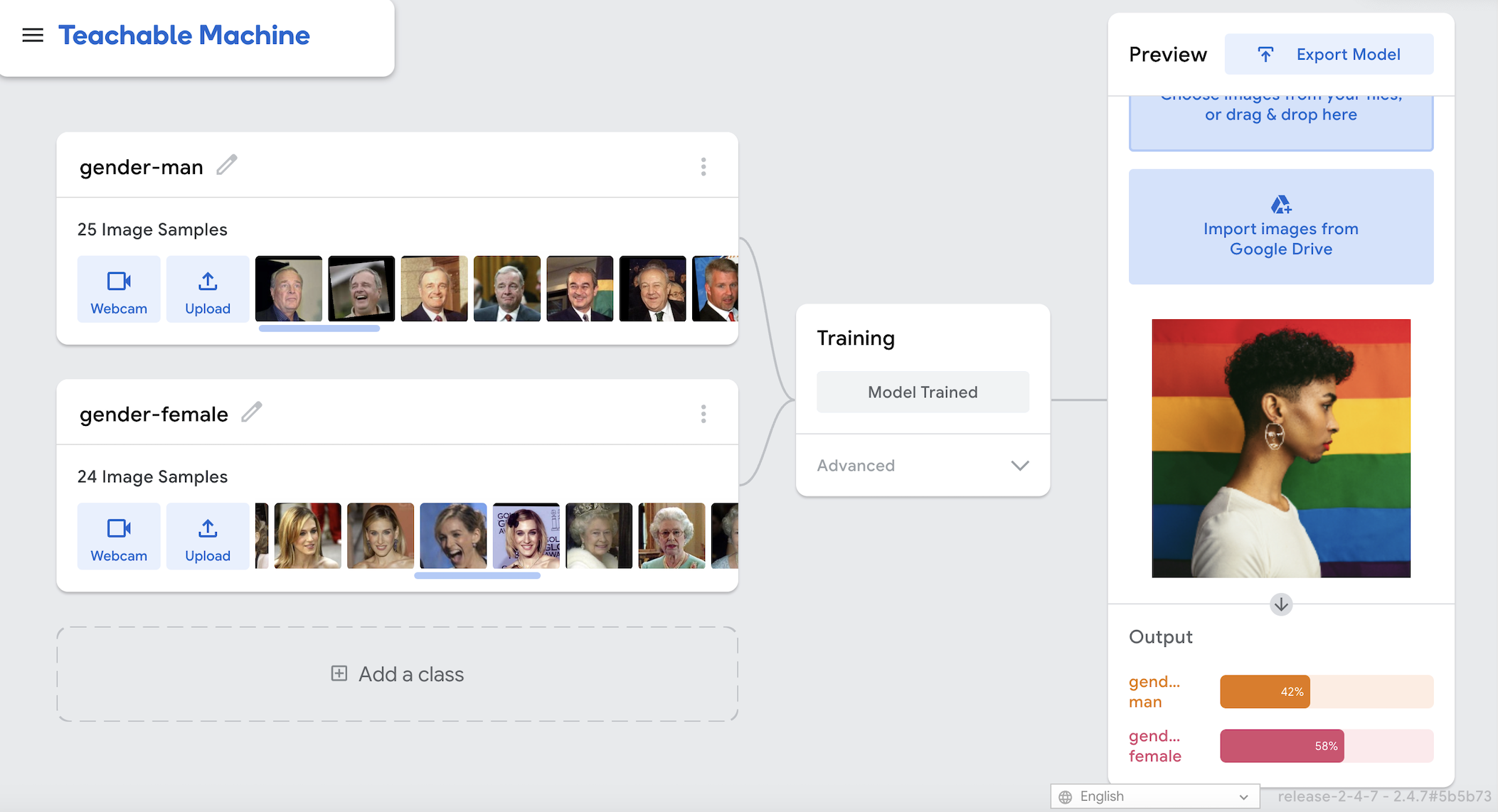

I realised that social media platforms are often seen as ‘tools’, but in fact they are not tools, they exist as a collection of power. In an algorithmic process, it makes some things visible while hiding others. Moreover, platforms also collect a lot of user data and content data, and they profit by automatically connecting users, data and adverts.

What's more, the data collected by platforms isn't exactly ‘raw’ when they design user interfaces and choose user features that largely guide the way users interact with each other. This results in pre-established data collection mechanisms that platforms can shape and trigger to collect pre-determined, structured data, which in turn influences the structure of the platform, which can choose to highlight certain parts of the content with an emotional slant, prompting the user to take action.

Dijck, J.v., Poell, T. and Waal, M.d. 2018. The platform society : public values in a connective world. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Hoffmann, A.L. 2018. Platforms of power Custodians of the Internet Tarleton Gillespie Yale University Press, 2018. 296 pp. Science (American Association for the Advancement of Science). 360(6394), pp.1193-1194.